Paul Bley is an interesting and elusive figure in jazz. Yet somehow it’s hard to even avoid hearing people talk about him and his music. Just the other day I came across a version of Jazz.com’s “The Dozens” featuring Aaron Parks on Paul Bley. “The Dozens” is an occasional feature that lets musicians and/or critics pick 12 tracks representative of a particular artist or theme. Sometimes the choices and commentary can be very bland (the Steely Dan Dozens is terrible), but there are also some very worthwhile and illuminating posts. One of those is Aaron Parks on Paul Bley.

Paul Bley is an interesting and elusive figure in jazz. Yet somehow it’s hard to even avoid hearing people talk about him and his music. Just the other day I came across a version of Jazz.com’s “The Dozens” featuring Aaron Parks on Paul Bley. “The Dozens” is an occasional feature that lets musicians and/or critics pick 12 tracks representative of a particular artist or theme. Sometimes the choices and commentary can be very bland (the Steely Dan Dozens is terrible), but there are also some very worthwhile and illuminating posts. One of those is Aaron Parks on Paul Bley.

I am by no means an expert on Paul Bley. I mean, how can you be? With over 130 recordings to his name, and having recorded everything form solo piano records to live synthesizer shows, Bley’s discography is one of the most physically and aesthetically daunting of any musician’s in the past century (Bley himself could only compare the sheer mass of his discography to that of Louis Armstrong). But still, I would say i’m pretty knowledgeable about his most important recordings. Yet Parks managed to come up with a list that I was mostly unfamiliar with, which is pretty exciting. And of course, no comprehensive Bley list could be complete without the famous solo on “All the Things You Are.” It’s interesting to hear Parks’ take on it.

I also recently came across a very interesting radio interview with Mr. Bley from 2000. This was my first time hearing the pianist speak, and I was surprised (based on a lot of the stories I’ve heard about him) at how cordial and open he was. It’s not uncommon for artists who have been around and through as much as Bley has to be quite obtuse and prevaricatory in interviews that ask pretty basic questions, but Bley was more than willing to answer very open-ended and straightforward questions regarding his own development and the effect other artists have had on him and expound upon similar topics in very concise ways.

There were a few moments in this hour-long interview that stood out:

- I’ve always known that Bley has had experience playing with a veritable ‘who’s who’ of jazz throughout his career, but I was amazed at the sheer breadth of individuals that he mentioned having been lucky enough to play with. They included Ben Webster, Lester Young, Charlie Parker, Don Cherry, Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, Sun Ra, Archie Shepp, Evan Parker, Jaco Pastorious, Pat Metheny, John Abercrombie and even poets Allen Ginsburg and William Burroughs. A lot of these weren’t just one-off’s either. He recorded with Parker, hired Don Cherry and Ornette coleman for a band that became Ornette’s famous quartet after Bley left, ‘discovered’ Pat Metheny and even mentioned being quite close with Miles Davis.

- Bley had an interesting take on the development of free jazz, which he mentioned twice. According to Bley, there were two stages in this development. One occurred in 1958, when jazz began to lose form. The other occurred in 1964, when it began to lose meter. He loosely associates Coleman and Cherry with the former, and Cecil Taylor and Archie Shepp with the latter.

- Bley also had an interesting take on the role of the piano in free jazz. He seems to agree with Keith Jarrett (or Keith Jarrett agrees with him) that it is ‘impossible’ to play ‘free’ on piano. In his interview with Ethan Iverson, Jarrett says that Cecil Taylor ‘did everything he could’ in this regard. Bley seems to agree, and the interviewer contrasts Bley’s approach with that of Taylor’s. Bley talks about how the challenge of the pianist when Ornette’s group came out was to create sounds with the piano that could be altered/adjusted after they were created (I’m assuming he means the act of bending notes/creating polytones with one sonic output). He then briefly explains the difference between trying to do this with the piano itself as oppossed to using prepared piano.

- Bley offers the most concise explanation of why jazz is considered “America’s classical music” that I’ve ever heard. Responding to a comment about how his most recent work sounds very much like the work of early 20th century European classical composers for piano (Schoenberg, Webern), Bley remarked that his music was innately separate from classical music because what we call “classical music” is actually European classical music. What he means by this is that these composers were of a European influence. Bartok, for example, derived a lot of his compositions from European folk music, and Tchaikovsky from Russian folk music, etc. Jazz musicians, on the other hand, draw their influence from American folk music. Thus it is immediately a different type of music, if not just in name only. So, even though some of it might sound similar to European Classical music (Bley’s later work in particular), it is by definition jazz because it has grown out of an American Folk tradition: the blues.

When I re-find the link to this radio interview, I’ll post it. It’s more than worth an hour of your time. This, in the meantime, is worth 6 minutes of your time for sure:

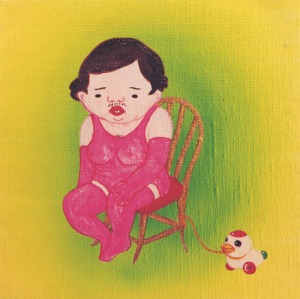

And again, think of what sum all of O’Rourke’s parts generates: Imagine Wilco meets Tortoise meets Sonic Youth meet Gastr del Sol with splashes of the Beatles and electronic surges straight out of Edgard Varese or Paul Lansky. That statement alone sounds overwhelming and seemingly impossible, but O’Rourke achieves it. It is easy, upon first listen, to discard this work as unambitious, considering what O’Rourke has strived for in the past, but that would be missing the point. O’Rourke might have expected such a reaction; after all, the title of the album seems to be a tongue-in-cheek reference to his own ‘backwards step’. But the beauty in this record actually lies in it’s ability to deceive. The music sounds so simple and familiar, but it is so rich in texture and individuality that the more one digs in, the more one realizes there isn’t anything else quite like it.

And again, think of what sum all of O’Rourke’s parts generates: Imagine Wilco meets Tortoise meets Sonic Youth meet Gastr del Sol with splashes of the Beatles and electronic surges straight out of Edgard Varese or Paul Lansky. That statement alone sounds overwhelming and seemingly impossible, but O’Rourke achieves it. It is easy, upon first listen, to discard this work as unambitious, considering what O’Rourke has strived for in the past, but that would be missing the point. O’Rourke might have expected such a reaction; after all, the title of the album seems to be a tongue-in-cheek reference to his own ‘backwards step’. But the beauty in this record actually lies in it’s ability to deceive. The music sounds so simple and familiar, but it is so rich in texture and individuality that the more one digs in, the more one realizes there isn’t anything else quite like it.