Kenny Wheeler is one of the most underrated jazz musicians of the last 50 years. The Canadian-born trumpeter’s decision to move to and remain in Britain for the majority of his life may have something to do with his lack of recognition, but when looking at his contributions to music it is hard to understand why he isn’t more well respected. Consider some of these quick facts:

Kenny Wheeler is one of the most underrated jazz musicians of the last 50 years. The Canadian-born trumpeter’s decision to move to and remain in Britain for the majority of his life may have something to do with his lack of recognition, but when looking at his contributions to music it is hard to understand why he isn’t more well respected. Consider some of these quick facts:

- Despite being mainly associated with post 1970‘s jazz, Kenny Wheeler is about a year younger than Horace Silver. That means he is older than Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Chick Corea, Keith Jarrett, and many other current ‘jazz elders’.

- Dave Holland’s first recording is on a Kenny Wheeler album. (This recording also features a young John McLaughlin).

- One of Keith Jarrett’s last dates as a sideman was on a Kenny Wheeler recording (over 30 years ago).

- Despite only making his recording debut at the age of 38, he has since appeared on almost 300 albums, ranging from the original soundtrack to Jesus Christ Superstar to albums by Philly Joe Jones, Joni Mitchell and Anthony Braxton.

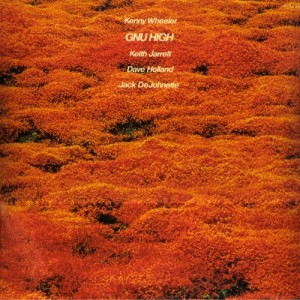

- His 1976 album Gnu High is one of the most popular jazz recordings of the 70’s. As Ethan Iverson pointed out in his list of the most important albums between 1973 and 2006, “This is one of those albums that everybody has.”

These notes seem to describe an extremely well-renowned musician, but unfortunately that is not a label we can apply to Kenny Wheeler. Many young musicians in America are unaware of his playing or his contributions to this music. There even remains a significant chunk of established jazz musicians who know little more than his name. My former teacher, the legendary Detroit trumpeter Marcus Belgrave, is among these musicians. But in addition to these quick facts, I can think of four major reasons why people should feel more inclined to check out this legendary trumpeter/composer.

1 ~~ His trumpet playing

Most people who consider themselves Kenny Wheeler fans will most likely admit they are more a fan of his composing and arranging than his trumpet playing. Among them would be Wheeler himself. Asked to comment about his own playing, Wheeler had an unusual response:

I’m not really crazy about my solos. Your solo is definitely down to you, and you only have a split second to decide what the next note is going to be. When you write a composition, a tune – whatever you like to call it – you can labour over it, change things, rub things out, until you like it. I do like a lot of my compositions, but in the end I don’t feel like I really own them. If you like, I have been lucky to tap into some source and picked them up, and I got them before anyone else did. I think Hoagy Carmichael said that about “Stardust”, he got it before anyone else got it. I have the same feeling about the tunes I write. I quite like them because I don’t feel responsible. But the solo, nobody is to blame but yourself.

But Wheeler is being modest. Other than Don Cherry, Kenny Wheeler may be the only trumpet player after 1950 to have no discernible influences; his style is truly original. Unlike Cherry, whose style was characterized by his lack of technique, Wheeler is an incredible technician. His style is often characterized by the lack of a clear bebop vocabulary and a penchant for placing large intervalic leaps within lines. Wheeler is one of those rare trumpet players who is as comfortable in the lead chair of his section as he is in the solo chair. Special recognition should go to him for maintaining his original style despite the influences around him. Even when playing standards on a Philly Joe Jones record in 1968 his style is completely his own.

With Anthony Braxton – “Composition 23J” – The Montreux/Berlin Concerts – 1975

His initial foray into the American market was when he was picked to join Anthony Braxton’s quartet in the early 70’s. His selection to join the band, as he states himself, was due to the fact that few other trumpet players could play the incredibly demanding parts that Braxton wrote. He is especially known for his flugelhorn playing, often preferring it over the trumpet, which is quite unusual. His sideman appearances have more often than not found him playing in a free setting, but he is just as comfortable navigating extremely complex chord changes, oftentimes written by himself.

2 ~~ His compositions

Wheeler is a prolific composer. Many of his own songs rarely appear more than once in his oeuvre, and if they do they more often than not they are unrecognizable compared to their original form (compare “Heyoke” from Gnu High to its appearance on the album Siren’s Song). Wheeler loves to really get inside his own compositions, to draw them out and expand upon them endlessly. This is the mark of a true composer, one whose works are constantly growing, forever developing. He has both an incredible knack for melody as well as a truly original understanding of harmony. His compositions bridge the gap between tradition and modernity: few would deny their categorization, yet they maintain almost no traditional harmonic movements. As I like to say, his chords are often “abstractions” of one another; they make little sense in terms of traditional concepts of harmonic movement yet make absolute perfect sense to the ear. This, to me, is a clear sign of a gifted composer; someone who can pull beautiful melodies and harmonies seemingly from nowhere and have it all make sense in the end.

“Bachelor Sam” – Windmill Tilter – 1968

Wheeler has released over 20 albums that almost exclusively feature his own compositions and he has recruited a wide array of established sidemen to help interpret them. Other than his consistent collaborators Dave Holland and John Taylor, Wheeler has collaborated with saxophonists Jan Garbarek, Michael Brecker, Lee Konitz, Evan Parker and Chris Potter, guitarists John Abercrombie, John McLaughlin, Bill Frisell and Ralph Towner, pianists Paul Bley and Keith Jarrett, as well as drummers Peter Erskine, Joe LaBarbera and Jack DeJohnette to record his own music. In more recent years he has been experimenting with a chamber sound, which initially was just a standard quartet without a drummer but later has involved both string and brass chamber groups.

3 ~~ His big band arranging

Kenny Wheeler has been most critically lauded for his big band work. His debut recording, Windmill Tilter, finds Wheeler’s abilities already fully developed. The compositions and arrangements, based around the story of Don Quixote, are all Wheeler’s and the band utilized is John Dankworth’s Orchestra, of which Wheeler was a member at the time. His complex notion of harmony is beautifully transferred to the orchestra and sounds amazingly fresh and modern considering it was recorded in 1969. There is nary a bad song on the album, and it is certainly a shame that we will never hear it remastered (the master tapes have been lost or destroyed), so if you can get your hands on it, don’t hesitate!

“Sophie” – Music For Large & Small Ensembles – 1990

Wheeler’s most famous big band date is certainly the 1990 release Music For Large and Small Ensembles which features, among many others, John Abercrombie, Peter Erskine, John Taylor, Evan Parker and Dave Holland. The album is the pinnacle of Wheeler’s big band writing, complete with his trademark of using Norma Winestone’s voice as a (often lyric-less) lead instrument. The “Sweet Time Suite” is a landmark in big band writing, which opens with an absolutely breathtaking chorale. There is very little traditional big band styles in his writing, which often sounds more classical than jazz-influenced while maintaining an unmistakably modern sound. “Sophie” is a clear indication of the various styles that Wheeler masterfully transcends. It begins with two chamber-influenced chorales, one featuring the brass section and the other featuring the sax section. Wheeler rarely writes rhythmically unison lines; the sax chorale in particular is full of well-utilized counterpoint and beautiful contrary motion. They give way to an unmistakably Steve Reich-influenced piano motif and then seamlessly into a quick latin groove. While there are certainly more reference points for Wheeler’s arranging (see: Gil Evans), much like his trumpet playing he has been able to develop a truly original big band style that has not been imitated since.

4 ~~ Gnu High

If there is one thing and one thing only to appreciate Kenny Wheeler for, it is his 1976 release Gnu High. I feel somewhat bad saying this, however, because unlike many of Wheeler’s other releases, Gnu High was somewhat a product of happenstance, much of which Wheeler is not happy about to this day. For what was his debut on ECM records, Manfred Eicher gave Wheeler two options for a piano player: Keith Jarrett or Chick Corea. Wheeler chose Jarrett, most likely unaware that Jarrett was not the easiest person to work with. Upon arrival, Jarrett was given about 11 possible Wheeler originals to look over for the recording. He came back to the trumpeter with 3 and said they were the only ones he could work with. Luckily Jarrett has good taste, and these 3 Wheeler originals stand as his most lasting compositions. “Heyoke” and “Gnu Suite” are both miniature suites and combined they total over 30 minutes of music. “Heyoke” has an especially unusual form, but one perfect for Jarrett. What was most likely written to be a short solo interlude between movements turns into almost 4 minutes of solo piano, and it is great to hear Jarrett wringing out the rich Wheeler harmony. There is also a lot of room for Holland to develop his own ideas, especially in the frequent rubato sections that separate melodies.

If there is one thing and one thing only to appreciate Kenny Wheeler for, it is his 1976 release Gnu High. I feel somewhat bad saying this, however, because unlike many of Wheeler’s other releases, Gnu High was somewhat a product of happenstance, much of which Wheeler is not happy about to this day. For what was his debut on ECM records, Manfred Eicher gave Wheeler two options for a piano player: Keith Jarrett or Chick Corea. Wheeler chose Jarrett, most likely unaware that Jarrett was not the easiest person to work with. Upon arrival, Jarrett was given about 11 possible Wheeler originals to look over for the recording. He came back to the trumpeter with 3 and said they were the only ones he could work with. Luckily Jarrett has good taste, and these 3 Wheeler originals stand as his most lasting compositions. “Heyoke” and “Gnu Suite” are both miniature suites and combined they total over 30 minutes of music. “Heyoke” has an especially unusual form, but one perfect for Jarrett. What was most likely written to be a short solo interlude between movements turns into almost 4 minutes of solo piano, and it is great to hear Jarrett wringing out the rich Wheeler harmony. There is also a lot of room for Holland to develop his own ideas, especially in the frequent rubato sections that separate melodies.

From “Gnu Suite” – Gnu High – 1975

Often considered one of Jarrett’s greatest sideman performances, Gnu High also features one of the most riveting quartet performances of the 1970’s. Wheeler’s performance is, true-to-form, understated yet beautiful. He is apparently unhappy with his own performance on the album, clearly a nod to possibly being outshone by Jarrett. (You can hear Jarrett stepping on Wheeler’s toes at 2:42 in “Smatter”. It is clear that Jarrett thought Wheeler’s solo was over and began to play. Wheeler, understated both in his playing as well as his personality, steps back a little and is unsure as to whether or not to give way. Wheeler’s last chorus is thus an awkward back and forth between himself and the pianist, before he quietly makes his way out.)

Regardless, it cannot be denied that what is for the most part an incredible group performance is certainly a result of the band feeling inspired by the wonderfully original compositions. A clear indicator of this (and possibly my favorite moment on the album) is halfway through “Gnu Suite” when the main melody arrives. The beautiful melody is perfectly interpreted the first time around by Jarrett, and then afterwards joined by Wheeler himself. The melody, which is certainly not ideally fit for trumpet (let alone flugelhorn), is perfectly executed by Wheeler and gives way to a masterful trio performance.

Gnu High remains a landmark recording, certainly one of the best jazz records of the 70’s, and a must-have for any fan of Jack DeJohnette, Dave Holland, Keith Jarrett, Kenny Wheeler, or of just music in general.

November 21st, 2009 at 3:09 pm

I spoke about missing Kenny Wheeler about two weeks ago (http://numinousmusic.blogspot.com/2009/11/where-is-kenny-wheeler.html) so I’m glad to see I’m not the only one who thinks he should be more recognized than he seems to be at present.